Featured image: Digital reconstruction of the Throne Room, Palace of Nestor. © Shannon LaFayette Hogue and Dorian Sanders

By John Leonard

Messinia, the increasingly popular, sun-drenched and unspoiled coastal region in southwest Peloponnese home to the renowned resorts of Costa Navarino, is also the latest hotspot in the exploration of Greece’s Late Bronze Age. Long recognized for its mythical, Homeric connections to ancient Greece, this was the home of “King Nestor of Sandy Pylos,” the legendary Mycenaean-era ruler who fought at Troy and once hosted Telemachus, Odysseus’ son, at the start of his search for his long-lost father. Some might argue all these stories are simply that – stories, myths, heroic tales. Yet this is where the unique magic of Greek archaeology enters.

Left: Minoan Signet Ring with Lion and Nursing Cow, 1520/10– 1360 BC, from Antheia, Tholos Tomb. Kalamata, Archaeological Museum of Messinia, AMM 3995

Right: Gold Mycenaean Necklace with Papyrus-Blossom Beads, 1410/00–1360 BC, from Antheia, Ellinika Chamber Tomb 4. Kalamata, Archaeological Museum of Messinia, AMM 4043

Antiquarians, pioneering archaeologists and today’s more scientifically-minded investigators have been able, over the years, to identify actual millennia-old sites and ruins that represent the seeds of truth sown into ancient myths and legends about Late Bronze Age Greece. The greatest recent archaeological development in Messinia, and Greece in general for many years, was the chance discovery of the stunningly intact burial of the so-called “Griffin Warrior,” recently highlighted in Kalamata in an exhibition organized by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Messinia (Hellenic Ministry of Culture) which is now traveling to the Getty Villa Museum in California under the title “The Kingdom of Pylos: Warrior Princes of Ancient Greece” before coming to Greece’s National Archaeological Museum in March 2026. This July, the lead archaeologists behind the excavations and creators of the exhibition catalog, Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker, will present their work at the amphitheater of Navarino Agora.

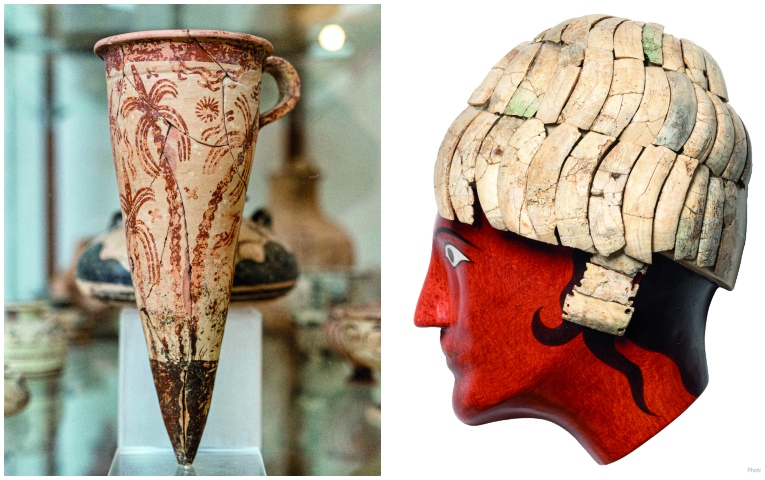

Left: Mycenaean Terracotta Conical Rhyton with Palm Trees, 1520/10–1450/40 BC, from Pylos, Chamber Tomb E8. Chora, Archaeological Museum, CM 2890

Right: Mycenaean Boars’ Tusk Helmet, 1520/10–1450/40 BC, from Psari, Tholos Tomb 2. Kalamata, Archaeological Museum of Messinia, AMM 11943

Unveiling ghosts in the kingdom of Pylos

In some ways, Greece is a world of ghosts, an inspiring, timeless land where today we walk among the shadows of real or imagined heroes, gods and goddesses, kings and queens, as well as other important past figures. Heinrich Schliemann came to Greece and the northern Aegean in the 1870s looking for seeds of truth in Homer and found them at Mycenae, Tiryns and Troy. In Messinia, however, he wasn’t so lucky, as he somehow overlooked clues that might have led him to another actual Bronze Age palace, this one located on a seemingly insignificant hilltop north of modern Pylos. It was only decades later that the Greek archaeologist Konstantinos Kourouniotis, who had already discovered Mycenaean tholos, “beehive” tombs, in the area, took an interest in the long-forgotten prehistoric site on Englianos Ridge.

Minoan Sealstone with a Battle Scene (The Pylos Combat Agate), 1630/10–1450/40 BC, from Pylos, Grave of the Griffin Warrior. Chora, Archaeological Museum, SN18-0112 © JEFF VANDERPOOL

Together with the American archaeologist Carl Blegen, Kourouniotis began excavating the hilltop in 1939 and unearthed a large, multi-roomed Mycenaean palace that we have now accepted was the real-life seat of prehistoric Pylos’ Nestor-like king (or “wanax”). After WWII, Blegen resumed the excavation of the Palace of Nestor (1952), while other foreign and Greek archaeologists, including William A. McDonald, Spyridon Marinatos, and George Korres, fanned out to explore the Bronze Age remains of the larger surrounding region. Today, following a decade of particularly intensive archaeological activity – not only on the Englianos Ridge but also at other sites across the ancient kingdom of Pylos (present-day Messinia) – the investigators’ remarkable achievements are offering new, intriguing insights into the complex international and culturally sophisticated world of the early Mycenaean period.

Previously overshadowed by the Argolid with its Cyclopean-walled citadels at Mycenae and Tiryns, Messinia is becoming the new focus of scholarly and visitor attention. Besides its many history-steeped Byzantine and crusader castles, Messinia can now boast an extraordinary array of Bronze Age sites, newly found or more thoroughly explored, and artifacts.

The Pylos Combat Agate is recognized as the finest example of Minoan or Mycenaean glyptic art yet discovered. A triangular composition is formed by the bodies of a victorious warrior (who wears such a sealstone on his wrist), his immediate opponent, and a warrior, already fallen on the field of battle, who lies beneath them. DRAWING © TINA ROSS

Warrior Princes

Among the most important finds are those from the shaft grave of the “Griffin Warrior” (about 1450 BC), unearthed in 2015-2016 in near-pristine condition beside the Palace of Nestor by archaeologists Sharon Stocker and Jack Davis of the University of Cincinnati. The name of this early grave – dating some 150 years before the Palace of Nestor (13th cent. BC – about 1180 BC) – comes from an ivory pyxis, buried with the deceased, on which appears a finely carved griffin: a mythical winged creature, half-eagle and half-lion. Also accompanying the deceased into the afterlife were his bronze weapons, ivory grooming implements, gold signet rings featuring minutely engraved figures, and many semi-precious sealstones, including a Minoan seal (the “Pylos Combat Agate”) that depicts, according to Stocker and Davis, “a heroic battle scene of incomparable artistic precision.”

One might wonder how such a magnificent discovery is still even possible in the 21st century, and why it took place here in Messinia. Who was the Griffin Warrior and why did he have such close connections with Minoan Crete? Given his exceptional display of funerary wealth, questions naturally abound. Was this long-haired, finely attired individual surrounded by symbolic images perhaps a priest? A king? A battle-seasoned elite somehow associated with local leadership? Although definitive answers to such musings may never come, the constellation of evidence being assembled from Mycenaean Messinia’s numerous high-status tholos tombs and other burials across the region provides clues.

While few Mycenaean graves have been found as intact and richly endowed as that of the Griffin Warrior, the sheer number and monumentalism of many Messinian tombs indicate the existence of a flourishing elite class. Moreover, the raw materials and stylistic techniques of their funerary gifts demonstrate these Mycenaean elites had close cultural and commercial ties with Crete and the East.

The characteristic sample of ritual and daily-life objects collected from eleven Messinian sites for the upcoming Warrior-Princes exhibition – including Linear B tablets, wall paintings, bronze and ceramic vessels, gold ornaments, a boars’ tusk helmet, a crown, two inlaid daggers, and imported and local personal adornments from two newly revealed beehive tombs beside the Palace of Nestor – points to local rulers such as “Nestor” cultivating broad networks of exchange. This window into ancient Pylian society illuminates the far-reaching advances and sophisticated tastes of the Mycenaeans, as well as the important and too-long-undervalued role that Messinia played in the Mycenaean world. Whoever the Griffin Warrior himself may have been, his remarkable persona, as evidenced by his possessions, shows how early and how strongly the potent culture of Minoan Crete had infiltrated the southwestern Peloponnese.

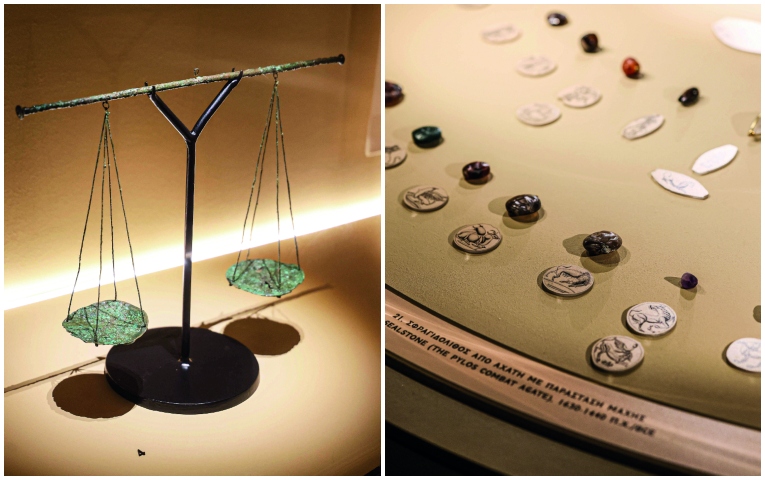

Left: Bronze balance. From Pylos, Grave Circle, Pit 4.1630/10–1410/00 BC. Chora, Archaeological Museum, CM 2076a–c. Temporary exhibition “Princes of Pylos. Bronze Age Treasures of Messinia” at the Archaeological Museum of Messinia, Kalamata. © NIKOS KOKKALIAS

Right: Sealstones from Pylos, Grave of the Griffin Warrior. 1630/10– 1450/40 BCE. Temporary exhibition “Princes of Pylos. Bronze Age Treasures of Messinia” at the Archaeological Museum of Messinia, Kalamata. © NIKOS KOKKALIAS

Mark your calendar

On July 17, 20.00 – 21.00 at the Amphitheatre of Navarino Agora, Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker, the lead archaeologists behind the excavations at the Palace of Nestor, will present their book “The Kingdom of Pylos: Warrior-Princes of Mycenean Greece,” by Melissa Publishing House. Prepare to plunge straight into the depths of the legacy that once shaped the Peloponnese.

The exhibition “The Kingdom of Pylos: Warrior-Princes of Ancient Greece” is currently hosted at the J. Paul Getty Museum – Getty Villa from June 25, 2025, to January 12, 2026, and then at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens from March 1 to June 30, 2026. Encounter the latest discoveries from Messinia, an epicenter of Mycenaean civilization in Late Bronze Age Greece, displayed for the first time outside Europe. Princely burials in monumental tombs reflect a society that came to be ruled by the Palace of Nestor in ancient Pylos.