By Tassoula Karaiskaki

The entrance to the mud-built courtyard of the palace complex automatically makes us feel a lot smaller. In front of us stands the Cyclopean Terrace, a gigantic platform made of boulders weighing four to six tons each. It’s four meters high, 25 meters long, and eight meters wide. Even today, 3,500 years after it was built, sections of white plaster with traces of red and blue paint are still preserved here and there.

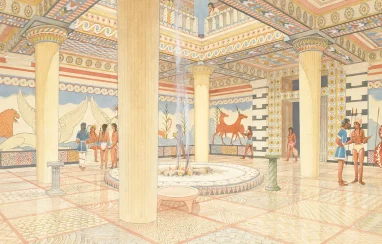

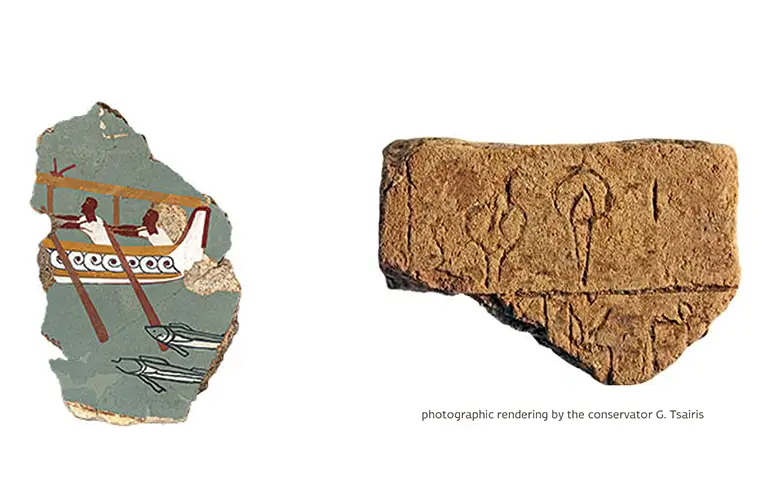

“This used to support a two or three-story building with impressive frescoes inside and some auxiliary rooms on the side. Elements such as the monumental character and the unique architectural form of the complex, as well as the excellent quality frescoes, are compatible with its use as an administrative center,” says Michael Cosmopoulos, a Professor of Archaeology and Director of the excavations at the Iklaina site, where we are standing. More than 2,000 fragments of frescoes have been found here, depicting subjects such as nautical scenes, hunting scenes, and ladies of the court in procession. The excavation is organized by the University of Missouri-St. Louis and conducted under the auspices of the Archaeological Society at Athens with the permission of the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports.

The site is located on a charming plateau that overlooks the Ionian Sea, where it’s believed that the first federal state in the Western world developed, sometime between 1600 and 1100 BC. We stroll the site from dawn until high noon, and Cosmopoulos draws our attention to the dimensions of the capital of a powerful Mycenaean state, the city of Iklaina, with its Cyclopean masonry, huge edifices, and impressive architecture, all brought to light by the archaeologist’s trowel.

With hoes, pickaxes, shovels, scrapers, spatulas, brooms, brushes, drones, tablets, and laptops, 45 out of the 60 participants working on this project are methodically digging up and scouring the soil (the remaining 15 work in a laboratory in Pylos, supervised by Cosmopoulos’ wife, zooarchaeologist Dr. Deborah Ruscillo). A day spent with the on-site team is like a dive into a long poem, an epic, an Iliad, an Odyssey, a Mahabharata, a Gilgamesh Epic – and an edifying experiential lesson on accurately approaching the distant past.

The foundations of the buildings that made up the city – the administrative structures, the houses (small mansions with central hearths), and the workshops – poke out into the light from the red soil. We move from what was once the residential and commercial part of the city and pass by the large cornerstones of a gate, heading towards the ancient administrative center, walking above the wide, perfectly preserved paved road now covered with special materials that protect it from temperature fluctuations.

“Buildings are almost on the surface. Many of them have never been buried and, for centuries, the inhabitants of the area have been finding ready-made building material here; ancient stones [from here] are found in houses, wells, and churches. So, in the archaeological site, there are buildings that end abruptly. There is one corner of a Mycenaean building here, another one there, and the rest has disappeared forever,” says Cosmopoulos as we cross a paved square from which a second paved road leads to an outdoor shrine. To the side, an almost intact stone-built sewer testifies to the advanced urban infrastructure. “The city,” the archaeologist notes, “had, from such an early date, a central drainage system with built-up sewers and a water supply network of clay pipes.”

Iklaina and the Kingdom of Nestor

Before us spreads a majestic landscape and, beyond that, the blue Ionian. The surrounding hills, a calm harmony of lines in shades of deep and silvery green, trail off into the vast sea. “There was visual contact with Nestor’s Palace. For a large part of the Mycenaean period, it appears that they were rivals, but they could see each other,” says Cosmopoulos.

Iklaina was an independent state, as confirmed by the discovery of the oldest Linear B tablet (1300 to 1350 BC), an excellent sample of Mycenaean bureaucracy, which is 100 to 150 years earlier than those found in the Palace of Nestor (1200 BC) “Our working hypothesis, ” says Cosmopoulos, “is that, for the greater part of the Mycenaean period, Messinia was divided into independent states – one of them being Iklaina and another being Nestor’s Palace. Around 1250 BC, the ruler of Nestor’s Palace began occupying the neighboring states, thus creating the Mycenaean state of Pylos.”

Given that each province had its own capital, government, and administrative center but all came under the central authority of the Palace, this seems to be the first recorded instance of two levels of government in Western civilization. This is suggested by new evidence coming to light at Iklaina, the only Mycenaean capital currently under systematic excavation. It seems that the new rulers of the area, through violent occupation and the destruction of monumental buildings, obliterated all signs of the former political power and relegated Iklaina to the status of a craft center. The workshops and warehouses here continued to be used for another 50 years and were only abandoned with the destruction of the state of Pylos, around 1200 BC.

Iklaina was such a radiant Mycenaean center that its memory seems to have survived for at least four centuries after its abandonment since it’s possibly mentioned by Homer in the Iliad. Experts believe it to be the same as Homer’s Aepy, one of Nestor’s nine cities said to have sent ships to the Trojan War. “The memory of Nestor’s mighty palace and its states, nine in the western and seven in the eastern province, had survived until the time of Homer,” Cosmopoulos says. “I believe that the preservation of the memory of the great kingdom of Pylos among the local populations was made possible through social memory processes. Buildings that have never been buried function as places of memory and, combined with oral tradition, contribute to the preservation of historical memory.”

Once the restoration at ancient Iklaina is completed, using all the materials that have been found in the area, two visitor routes are going to be created. One will be inside the fence, following the streets taken by residents of the ancient settlement, and one will be a raised walkway outside the barrier so that visitors can see the site even when it is closed. They will also be able to download an app that highlights the different parts of the restored city, helping them to gain a clearer picture as they travel back in time.

[Photo Credits: © Nikos Kokkalias]